In hindsight, it’s comical and allegorically appropriate that the first Oslo Triennale took place underground. The title of my essay “Underjordiske inspirasjoner” indeed translates into “Underground inspirations”, but it also hints at something more mythical and maybe culturally suppressed – as something closer to subterranean imaginations. It was a superb show, and the venue almost sublime.”

Back in 2000, Mari Lending was a critic of words and literature rather than buildings and landscapes, but having just received a PhD grant in aesthetics, she was preparing to base herself in the architecture school to research and write her dissertation. Oslo Architecture Triennale invited Lending to develop the catalogue for their first year, the academic presuming she was being asked in the hope her connections with journalists and critics would help with wider cultural awareness of the festival – though Lending bluntly suggests this outcome “was not really successful”.

True or not, it speaks to Oslo Architecture Triennale’s [OAT] early ambition to take the subject of the built environment out into other discourses, enmeshing it within wider cultural conversations and discussions of the day, rather than retreating into the immaculately detailed ivory tower of architecture, in which architects talk to other architects in codified language.

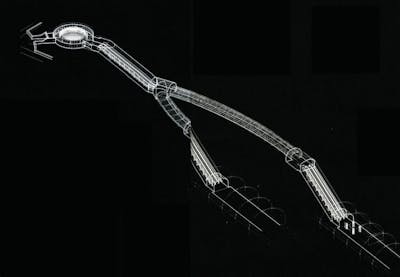

“The first Triennale took place in the bowels of Oslo, so to speak: in an empty space somewhere below, I believe, the new subway station below the royal palace and the Ministry of Foreign Affairs. This was, and still is, a secret space – thinking back now I don’t completely understand where it was or where the entrance was. Being present during the mounting of the enormous exhibits and during the show felt like a profound experience of descending into something unknown and unforeseen. Looking at these both conceptual and partly ironic interpretations of a future Oslo, felt like being somehow outside both time and place.”

Today, twenty years on, one could look back and think that to locate the opening exhibition in a secret underground chamber would go against the idea of opening up the discussion. But there is a logic. The public discourse of architecture has always predominantly been about that which projects skywards: glass towers; cranes jigsawing architectural components together; arguments around future aesthetics; and new cultural spaces opening up new ways of seeing and being seen. But much of architecture is under the surface. In Oslo it’s not just the caves of the Metro, but also basements, tunnelling, service spaces and guts of the city – normally out of sight even to the most devout architectural aficionados.

So inviting everyone into such a neutral and other

underground space could divert some of the predicted mannerisms, behaviours and hierarchies into the search for a new public engagement, away from the existing view of the city, the rigidity of time, and the expectations of convention.

“Anyway, even though the space and the projects were very real, the metaphor of the underground perfectly captured something that has changed a lot over the last two decades. At the time there was hardly any public debate on architecture in Oslo, except for a few distinct conservative voices, with idiosyncratic views on architecture, the city and the world, and with marginal interest in conceptual contemporaneity. So that is a substantial change in the Norwegian public sphere, that architecture, the most public of the arts, is now part of the public debate – as it used to be in the late nineteenth century, or in the 1920s and 30s. Obviously, architecture did belong to the underground two decades ago. It really feels like a long time ago.”

I write this from my home in London, a city which more than any other bears the decorative scars of neoliberalism through monumental architecture – expressive spectacles of shining ‘iconic’ forms, questionable erections and depositories (suppositories?) of luxury capital. The aesthetic of such neoliberal monuments began with the 1986 “Big Bang” of financial deregulation, ushering in four decades (so far) of free-marketisation demanding a built form which reflected its supposed values of success, power, awe and opportunity, beginning with Canary Wharf and Docklands. We gave the invisible hand of the free market a Rotring pen, and it drew us a skyline of monuments to speculative finance and luxury. In the same year, the British state disposed of its North Sea oil rights to private businesses.

With its oil income, Norway created “the State‘s Direct Financial Interest” and later, “the Sovereign Wealth Fund”. Norway invested its wealth in the foundations of the State and, as Lending explains, into tunnelling infrastructure and ever-deeper drilling in ever-wilder landscapes. In her catalogue essay, Lending talks of an “inverted monumentality”, and how Oslo is a capital which places its large and important buildings in “narrow streets” unlike the spectacular approach of London, and I asked Lending about this idea of the monumental, and what it means in Norway.

“Monumentality has never been a Norwegian obsession, in the classical sense, in regard to architecture. I’ve often thought that there is a peculiar national tradition at work here, which in the postwar period (not least after the oil, obviously) was expressed by pouring wild amounts of money and political ambition into monumental infrastructure in the boonies, for example drilling insane – or bold, if you prefer – tunnels through mountains. In the Norwegian context, the sublime has been more about the interior of the mountain than about the view from the top. Another facet of the same phenomenon was building unprecedented structures in the North Sea, predictably in the form of oil platforms. The display of money, ambition and power has largely taken place where nobody could really see it. Snøhetta’s Opera partly changed that. The opera dates back to the same year as the Oslo Triennale, a building that has received its share of attention. A new sense of monumentality has emerged, with the Oslo waterfront as probably the most conspicuous example, draining cultural institutions throughout the city, leaving behind vacant but wonderful architecture, with the activity and display of prestigious buildings at the waterfront. It sometimes makes one think that the whole city is about to tip into the water.”

In her essay, Lending writes beautifully about the roots of the Greek word “krinein”, from which the Norwegian and English words “criticism” and “crisis” have both evolved. She invokes an old and near-forgotten variant of krinein, in Norwegian vederkvegelse, i.e. revival, which is to “touch and to be touched in the same movement and in the same word”. It suggests a kind of empathetic, democratic but critical idea of the city, an Oslo which has open discussions about its concerns and its futures, which does not just present the image of engagement, but instead has meaningful, informed conversations. Back in 2000, Lending wrote that “conversations about Oslo, often called debate, are is rarely characterised by drama, struggle or articulated tension: Oslo’s development takes place in silence.”

Noting that after 2000’s opening Triennale the conversations and dialogues of the city began to rise out of the silent caverns, just as Snøhetta’s winning design foreshadowed the Barcode developments and the emergence of a city built less around narrow streets and more around a mediatable global aesthetic, I discussed with Lending what has changed over twenty years, and what is next.

“The 2000 Triennale was scarcely critiqued or debated outside professional circles, and it hardly has a public reception history. It was a grand initiative, and the work of a small group. The architecture exhibition was not really a format the public or the critics were trained in. That has certainly changed a lot. Across the world, the field of architecture has been radically expanded throughout the last few decades, involving lots of research on architectural exhibitions, publications, and all sorts of media that constitute architecture, professionally and publicly. In the Norwegian context, architectural exhibitions from the nineteenth century on have also been unearthed from the archives. That is of course one context for the Oslo Triennale too; we simply have more knowledge about these display formats, and a much bigger and better informed public to react critically to such initiatives.”

“Today, there is a different climate where lots of people want to engage with the public face of architecture. There is a profound interest in the development of the city today. We also see this in my school, the AHO, and it is really nice that the Triennale has become such an important part of our school’s inner life.”

If the inspiration for 2000’s Triennale emerged from the underground, twenty years later OAT is determinedly above ground, in the agora. But will it always remain so? Perhaps we now – in Oslo, London, and all over – face a different problem relating to engagement and the work of the city. At a time of climate breakdown, economic precarity, and rising authoritarianism is there a concern that conversations which had been brought into the open will again return to silent subterranean echo-chambers? In a landscape of digital communication bubbles and bunkers built by preppers, society is on the point of fragmenting, and in the process of severing hard-earned links among disciplines, communities, ideas and futures.

Lending is concerned that Oslo may tip into the water. What a shame it would be if it simultaneously submerged the discussions and ideas that have grown over two decades – if a new economic and political landscape foreclosed conversation, and architects returned to ivory towers as protection from surrounding criticism and crises.

Lending closed her 2000 catalogue essay, “The best way to respond to a critical condition is with a critical sense and a sense of criticism: the city stands at a point where you know it will change, but you do not know which direction the change will take.” This is perhaps an eternally valid statement for Oslo and all cities, and at times of critical conditions it is easy to conceal it and retreat into the bunker, to regress to the cultural repression of caves. But it is probably the most important time to stay public, open and engaged. To touch and be touched.

In this series of seven interviews, one for each iteration of the triennale, the British architectural writer Will Jennings is exploring some of the individuals, places, ideas and actions that have shaped twenty years of OAT. Will Jennings was selected to participate in the jubilee through an open call in collaboration with Future Architecture Platform.