VISJONER FOR HOVEDSTADEN

Scroll down for English.

I dag slutter ikke lenger byen på Jernbanetorget ved enden av Karl Johans gate, slik den gjorde i 2003. Den seksfelts motorveien gjennom byen er forlengs lagt i rør under vannet.

Når vi i dag, 17 år senere, krysser Stasjonsallmenningen, ser vi inn på byens arkitektoniske treenighet, Operaen, Deichmann og Munchmuseet, med en stor vannflate i forgrunnen. Dronning Eufemias gate åpner seg grønn og generøs østover. Barcode, Dronninglunden, Vannkunsten og Sørenga danner en ny og levende bydel. Den sammenhengende havnepromenaden og nye badeplasser trekker folk til vannet.

Byen for 20 år siden. I 2003 var arbeidet med Fjordbyplanen godt i gang og i august samme år ble den overordnede reguleringsplanen vedtatt. Selve Fjordbyplanen ble vedtatt først i 2008. Dette var vedtak som skulle skape kanskje den største forandringen i Oslo siden Christian kvart grunnla Christiania og flyttet byens sentrum fra øst til vest i 1624. Tiden rundt 2003 var preget av en stor optimisme og vilje fra politikere, planmyndigheter og arkitekter til å skape en fundamental endring i Oslo.

Forslaget fra arbeiderpartipolitikeren Britt Hildeng om å flytte Operaen til Bjørvika, etter at det for lengst var enighet om at den skulle ligge på Vestbanetomten, var dramatisk, men meget godt. Det førte til at tyngdepunktet i byen rykket østover og bokstavelig talt ut i vannet. Mange mente at det ville svekke Oslo sentrum, som ville bli for stort for en by av Oslos størrelse.

På samme tid var flere andre meget store og definerende prosjekter rundt om i Oslo på tegnebordet. Lørenbyen, Ensjøbyen og Kværnerbyen med storskala boligutvikling. Tjuvholmen, Operaen, Vestbaneutbyggingen, utbyggingen på det gamle Rikshospitalet og flere viktige miljøprosjekter, bl.a. åpningen av Alnaelva.

Triennalen. Alt dette var bakteppet for Oslo arkitekturtriennale 2003. Landsstyret i NAL ønsket å sette fokus på den enorme transformasjonen Oslo sto overfor. Vi ønsket at triennalen skulle rette seg mot Oslos og landets innbyggere for å formidle hva som var på gang i hovedstaden, og derigjennom skape debatt og engasjement. Vi så mulighetene for at Oslo kunne bli en europeisk «arkitekturhovedstad», og vi ønsket å bevisstgjøre folk flest på den viktige, samfunnsbyggende jobben arkitektene gjør. På den tiden var det en del negativt fokus på arkitekten i den offentlige debatten – ofte knyttet til kvaliteten på boligområder og moderne arkitektonisk uttrykk. Vi mente at et bredt fokus på arkitektens rolle i byggingen av det nye Oslo vil bidra å bygge tillit og omdømme for vår profesjon.

Vi ønsket at triennalen skulle være ekstrovert og henvende seg til det generelle publikum og politikerne, så vel som til arkitektene. Noe mer i retning av en bred arkitekturfestival, i motsetning til den mer introverte og utopiske første triennalen. Også i motsetning til flere av de påfølgende triennalene, som har blitt smale og litt høytflyvende akademiske, med en noe begrenset appell både blant arkitekter og det generelle publikum. Slik sett fremstår triennalen i 2003 som annerledes enn de øvrige.

Vi ga den tittelen Visjoner for hovedstaden, og programmet for triennalen ble utviklet gjennom brainstorming i NALs landsstyre, i et arbeidsutvalg som ble etablert og med viktige bidrag fra arkitekt Line Bull, som ble engasjert som prosjektleder. Viktige bidragsytere var Norsk Form, Bolig- og byplanforeningen, Byantikvaren, OAF, NIL, NLA, AHO, Galleri ROM, Arkitekturmuseet, kulturbåten Innvik og A-track. Med unntak av triennalekonferansedagen rettet alle arrangementene seg direkte både til publikum generelt og til arkitektene. På Karl Johan vaiet bannere som kunngjorde Arkitekturtriennalen.

Triennaleutstillingen. Vi arrangerte en bredt anlagt Triennaleutstilling i skur 39 ved Akershusstranda, som i ettertid ble konvertert til kontor for Snøhetta. Prosjektleder for utstillingen var arkitekt Erik Urheim. Hensikten var å rette oppmerksomheten mot det store skiftet Oslo sto foran og samtidig skape debatt om prosjektene og helheten i utviklingen av nye Oslo.

Utstillingen hadde en rekke sponsorer som stilte seg bak sine prosjekter:

- Plan- og bygningsetaten presenterte Fjordbyplanen, Bjørvika og Groruddalsatsningen.

- OBOS presenterte Pilestredet park (Arkitektkontoret GASA og Lund & Slaatto Arkitekter), Marienlyst park (Lundhagem), Sjølyststranda (LPO og 4B Arkitekter), Fredensborg (Dyrvik Arkitekter), Lakkegården (Arkitektskap) og Kværnebyen (ARCASA Arkitekter).

- Statsbygg viste Vestbaneutbyggingen, Regjeringsbygning R5.

- Vann- og avløpsetaten presenterte Alnavisjonen, med gjenåpning av Alna på Hølaløkka.

- NCC viste Akerselva Atrium, Helsfyr Panorama, Fyrstikkalleen, Brynseng Park og Lysaker Torg.

- Linstow presenterte Barcode med DARK, MVRDV og A-Lab.

- Forsvarsbygg viste den nye bygningen for Forsvarsdepartementet på Akershus.

- Entra, Selvaagbygg viste Tjuvholmen (Torp+) og Lørenbyen (Nordic).

- EUROPAN 7 var sponset av NAL og vist 107 innleverte forslag på tomter i Oslo.

- Oslo Havnevesen viste planene for Akershusstranda, etter designkonkurransen som ble vunnet av Lund Hagem.

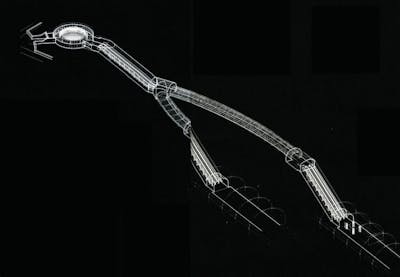

- Tre grupper utarbeidet på bestilling fra NAL sine visjoner for hovedstaden. Det var DARK, Plan-B og Helen & Hard som bidro til nytenkning og debatt med sine presentasjoner.

Landsstyret hadde som en av sine fanesaker å arbeide for å styrke den bærekraftige utviklingen og å øke arkitektenes kompetanse innen dette feltet. NALs Senter for bærekraftig arkitektur og stedsutvikling, NABU, presenterte nyvinnende konsepter, prosjekter og stedsutvikling fra de nordiske land, som pekte videre mot det som i dag er blitt en etablert og integrert del av arkitektenes praksis. Det ble etablert kontakt med Oslo kommune om å arrangere en boligutstilling med fokus på bærekraft, noe som ble en forløper til FutureBuilt.

Den brede presentasjonen av planer og prosjekter ga et meget godt inntrykk av det paradigmeskiftet Oslo stod foran. Fra å være en relativt stille og beskjeden hovedstad, til å bli byen «mellom det blå og det grønne», som byplankontoret beskrev det, med rekreasjonsområder, aktivt byliv og høy standard på arkitektur og byrom. Det meste er nå, 17 år senere, i stor grad gjennomført. Det oppsto en meget følelsesladet debatt om mange av forslagene. Barcode ble beskrevet som en massiv mur som stengte byen ute fra vannet. DogA innkalte til krisemøte for å diskutere Dronning Eufemias gate, som med sin bredde på 42 meter ville sprenge Oslos målestokk!

Larven. Vi ønsket å markere Oslo arkitekturtriennale 2003 med en installasjon på et sentralt sted i byen. Hensikten var å lage en fysisk manifestasjon, som med humoristisk form og farge som skulle gjøre folk nysgjerrige og markere at det var arkitekturfest i byen. Arkitekt og senere professor Magne Magler Wiggen ble engasjert til å designe en installasjon som skulle plasseres ved Rådhusplassen. Den skulle utformes for å kunne trekke publikum inn og igjennom installasjonen. Alle som kom inn ble utfordret til å skrive ned sine forslag til hva som kunne gjøre Oslo til en enda bedre by. Resultatet ble «Larven», en hvit og oransje pneumatisk larveformet struktur med inn- og utgang i hver ende og hundrevis av «idélapper» fra publikum festet til nedhengte klips fra taket.

Andre arrangementer under triennalen var blant annet «Åpent hus», hvor byens beboere ble invitert inn i offentlige og private bygninger, noe som i etterfølgende år er blitt et veldig populært tilbud med stor publikumstilstrømning. Vi arrangerte også flere arkitektoniske byvandringer.

Triennalekonferansen.

Triennalekonferansen hadde søkelys på Oslos byutvikling, med forelesere som presenterte relevante referanser fra andre byer. Åpningsforedraget ble holdt av daværende kommunalminister Erna Solberg. Hun satte søkelys på fremtidens Oslo som en multietnisk og multikulturell by, og behovet for å la det påvirke måten vi utvikler byens sentrum på, og hvordan vi utvikler våre boliger. Hennes budskap var viktig, men vi må vel fortsatt konstatere at mye mer kan gjøres for å sikre gode bo- og leveforhold for veldig mange av byens innbygger fra ulike kulturer og ulikealdersgrupper.

Oslo kommune inviterte til mottakelse i Oslo rådhus. Ordfører Per Ditlef Simonsen, som også var til stede ved triennalens åpning, berømmet NAL for å sette utviklingen av hovedstad på plakaten og understreket viktigheten av arkitektenes rolle i arbeidet for å få den byen vi ønsker oss. Han gjentok NAL-presidentens utsagn om at Fjordbyprosjektet er det største byplangrepet siden Christian kvart.

Etter mottakelsen i rådhuset holdt NAL «Åpent Arkitektenes hus», med stor deltakelse og sosial mingling og diskusjoner til langt på natt.

Oppsummering og videre planer. I evalueringen av Oslo arkitekturtriennale 2003 konkluderte vi med at vi var svært godt fornøyde med programmet, som satte fokus på det store skiftet Oslo sto ovenfor, og at vi klarte å rette fokus mot byutvikling og de mange enkeltprosjektene som var på gang. Det var gode diskusjoner med påfølgende debatter. Vi mente vi nådde frem både til publikum og til fagmiljøet.

Publikumsdeltakelsen var god, med et samlet besøkstall et sted mellom 10.000 og 15.000.

Vi konkluderte med at vi kunne fått enda flere deltakere og fått til enda mer publisitet, debatt og oppmerksomhet rundt triennalens innhold dersom vi hadde hatt større muskler. NAL hadde med seg mange gode bidragsytere, men stod likevel alene som arrangør. Det var meget krevende for alle involverte, ikke minst for NALs administrasjon ledet av Hans H. Halvorsen. Det krevde mye frivillig innsats og finansieringsarbeidet var slitsomt.

Vi mente at triennalen hadde et stort potensial, men for å kunne ta det ut ville det være nødvendig med flere medeiere og en mer robust finansiering. Triennalen 2003 hadde en meget anstrengt økonomi. Prosjektledelsen og administrasjonen i NAL gjorde et stort arbeid for å tiltrekke seg økonomisk deltakelse og støtte til de enkelte arrangementene. NAL stilte selv en økonomisk garanti på 240.000 kroner for å dekke den gjenstående usikkerheten i finansieringsplanen.

Neste triennale. I 2005 igangsatte landsstyret planleggingen av Oslo arkitekturtriennale 2006. Vi var enige om å videreutvikle triennalen som en arkitekturfestival som bygget opp under Oslos image som «arkitekturhovedstad» og at dette skulle komme frem i triennalens tema. «Arkitektur og kultur» var nevnt som en mulighet. Målgruppen skulle være det generelle publikum, politikere, arkitekter og planleggere. Målet var å informere, skape debatt og sette søkelys på arkitektens virke.

Vi signaliserte overfor Oslo kommune vår positive interesse for en boligutstilling i Oslo som kunne få tilknytning til kommende triennaler. NAL søkte kulturdepartementet om 500.000 kroner til videre planlegging av triennalen 2006. Norsk Form meldte sin interesse for å delta som arrangør. Det var enighet om å prøve å trekke inn flere medarrangører. Gjennomføringen av Oslo Arkitekturtriennale 2006 skulle bli ansvaret til den nye presidenten og landsstyret som tiltrådte i 2006.

Visions for the Capital

Text by Gudmund Stokke

Today, the city no longer stops at Jernbanetorget at the end of Karl Johans gate, as it did in 2003. The old six-lane motorway through the city has long since been laid in tubes underwater.

When we cross the central station common, Stasjonsallmenningen, today, 17 years later, we get a view of the city’s architectural trinity – the Opera, Deichmann Library and the Munch Museum, with a large body of water in the foreground. Dronning Eufemias gate opens up generous and green to the east. Barcode, Dronninglunden, Vannkunsten and Sørenga form a new and vibrant district. The continuous harbour promenade and new bathing spots draw people to the water.

The city 20 years ago. In 2003, work on the Fjord City plan (Fjordbyplanen) was well underway, and in August of the same year, the zoning plan was adopted. The Fjord City plan itself was not adopted until 2008. These two resolutions were to give rise to what may be the most far-reaching change in Oslo since King Christian IV founded Christiania and moved the city centre from east to west in 1624. The years around 2003 were filled with a great deal of optimism and willingness on the side of politicians, planning authorities and architects to bring about a fundamental change in Oslo.

Norwegian Labour Party politician Britt Hildeng’s motion to move the Opera to Bjørvika, after it had long been agreed that it would be located on the Vestbanen site, was a dramatic but extremely solid proposal. As a result, the city’s centre of gravity shifted toward the east and literally into the water. Many believed that it would weaken the centre of Oslo, which would grow too large for a city of this size.

At the same time, a number of other major and defining projects all around Oslo were on the drawing board: Lørenbyen, Ensjøbyen and Kværnerbyen with large-scale housing developments. Tjuvholmen, the Opera, the development of Vestbanen and the old Oslo University Hospital and several important environmental projects, including the opening of Alnaelva.

The Triennale. All this formed the backdrop for the Oslo Architecture Triennale 2003. The national committee of the National Association of Norwegian Architects (NAL) wanted to put the spotlight on the enormous transformation Oslo was facing. We wanted the Triennale to address the inhabitants of Oslo and the entire country in order to convey what was happening in the capital, and thereby promote debate and engagement. We saw the potential for Oslo to become a European ‘architecture capital’, and our wish was to raise awareness among the general population about the important, community-building work of architects. At the time, architects were receiving a good deal of negative PR in public debate, often linked to the quality of residential housing and modern architectural forms of expression. We believed that a broad focus on the architect’s role in designing the new Oslo would contribute to building trust and boosting the reputation of our profession.

We wanted the Triennale to reach out and address the general public, politicians, as well as architects. Something in the direction of an architecture festival for the people, rather than the more introverted and utopian first Triennale, and in hindsight a contrast to several of the subsequent festivals, which turned into more specialized and academically rather ambitious events with a somewhat limited appeal to both architects and the general public. In this sense, the 2003 Triennale stands out from the others.

We chose the title Visions for the Capital. The programme itself was developed via brainstorming by a specially appointed NAL working committee, with important contributions by architect Line Bull, who was engaged as project manager. Important contributors were Norsk Form, the Norwegian Housing and City Planning Association (Boby), the Cultural Heritage Management Office (Byantikvaren), Oslo Association of Architects (OAF), Norwegian Organization of Interior Architects and Furniture Designers (NIL), Norwegian Association of Landscape Architects (NLA), Oslo School of Architecture and Design (AHO), ROM, National Museum – Architecture, Kulturbåten Innvik and A-track. With the exception of the Triennale’s conference day, all events were directly aimed at both architects and the general public. On Karl Johans gate, Oslo’s main thoroughfare, banners were waving in the wind announcing the Triennale.

The Triennale exhibition. We arranged a broadly conceived Triennale exhibition at Skur 39, Akershusstranda, which was later converted into an office for the architecture firm Snøhetta. The project manager for the exhibition was architect Erik Urheim. The aim of the exhibition was to draw attention to the major changes facing Oslo while at the same time sparking off a debate about the projects and the overall development of the ‘new’ Oslo.

The projects presented in the exhibition were each associated with a sponsor or sponsors:

- The City of Oslo Planning and Building Services presented the Fjord City plan, Bjørvika, and the Groruddal initiative.

- OBOS presented Pilestredet park (architecture firm GASA and Lund & Slaatto Arkitekter), Marienlyst park (Lund Hagem), Sjølyststranda (LPO and 4B Arkitekter), Fredensborg (Dyrvik Arkitekter), Lakkegården (Arkitektskap) and Kværnebyen (ARCASA Arkitekter).

- The Norwegian Directorate of Public Construction and Property, Statsbygg, showed the development of Vestbanen, Government Building R5.

- The Oslo Municipality Water and Sewage Administration presented Alnavisjonen, with the reopening of Alna at Hølaløkka.

- NCC showed Akerselva Atrium, Helsfyr Panorama, Fyrstikkalleen, Brynseng Park and Lysaker Torg.

- Linstow presented Barcode with DARK, MVRDV and A-Lab.

- Forsvarsbygg, the Norwegian Defence Estates Agency, showed the new building for the Ministry of Defence at Akershus.

- Entra and Selvaagbygg, showed Tjuvholmen (Torp+) and Lørenbyen (Nordic).

- EUROPAN 7 was sponsored by NAL and presented 107 submitted proposals for different sites in Oslo.

- Oslo Port Authority showed plans for Akershusstranda in connection with a design competition won by Lund Hagem.

- Commissioned by NAL, three groups submitted their visions for the capital: DARK, Plan-B and Helen & Hard. Their presentations contribued to innovation and debate.

One of the NAL national committee’s flagship issues was to work on strengthening sustainable development and to raise the competence of architects in this field. NAL’s Centre for Sustainable Architecture and Urban Development, NABU, presented innovative concepts, projects and local developments from the Nordic countries, pointing ahead to what now has become an established and integral part of architectural practice.

A building exhibition with focus on sustainability was arranged in cooperation with Oslo municipality, an event that became the precursor to FutureBuilt.

The broad presentation of plans and projects provided a vivid impression of the paradigm shift facing Oslo. From being a relatively quiet and modest capital, Oslo was turning into the ‘city between blue and green’, as the city planning office described it, with recreational areas, an active urban life and a high standard of architecture and urban spaces. Now, 17 years later, most of these plans have largely been completed. Many of the proposals sparked off an extremely emotional debate. Barcode was described as a massive brick wall that cut the city off from the water. DogA called an emergency meeting to discuss Dronning Eufemias gate, which would far exceed Oslo’s proportions with a width of 42 meters

Larven. We wanted to mark the 2003 Oslo Architecture Triennale with

an installation in a central location in the city. Our goal was to

devise a physical manifestation that, by using a humorous form and

colourful design, would arouse people’s curiosity and mark the fact that

the city was celebrating an architecture festival. Architect, and later

professor, Magne Magler Wiggen was commissioned to design an

installation to be exhibited in City Hall Square (Rådhusplassen). Its

design was to draw the audience inside and all the way through the

installation. Everyone who entered was encouraged to write down

suggestions for what would make Oslo an even better city. The result was

‘Larven’, a white and orange pneumatic larva-shaped structure with an

entrance and exit at each end and hundreds of the visitors’ ‘idea

scraps’ attached to clips suspended from the ceiling.

Other events during the Triennale included ‘Open House’, in which the

city’s residents were invited to visit public and private buildings, an

event that in subsequent years has become a very popular offering with

large crowds attending. We also arranged several architectural city

walks.

The Triennale conference. The conference focused on Oslo’s urban

development, with lecturers presenting relevant information from other

cities. The opening speech was given by the Minister of Local Government

at the time, Erna Solberg. She focused on the future of Oslo as a

multi-ethnic and multi-cultural city, and the need for this to be

reflected in the development of the city’s centre, as well as our homes.

Although her message was important, it must be noted that far more can

still be done to ensure good life and living conditions for a large

number of the city’s residents from different cultures and age groups.

Oslo Municipality held a reception in Oslo City Hall. Mayor Per

Ditlef Simonsen, who also attended the opening of the Triennale, praised

NAL for putting a spotlight on the development of the capital, and

emphasized the importance of the architect’s role in creating the kind

of city we want. He reaffirmed the statement by NAL’s president that the

Fjord City project is Norway’s largest urban planning enterprise since

Christian IV.

After the reception, NAL held an ‘Open Architects’ House’ with many

participants, social mingling, and discussions late into the night.

Summary and future plans. Our evaluation of the Oslo Architecture

Triennale 2003 concluded that we were quite satisfied with the

programme, which had revolved around the major changes facing Oslo, and

that we had managed to focus on urban development and the many

individual projects that were underway. We had fruitful discussions with

subsequent debates, and we felt that we had reached the audience as

well as the professional community.

Audience participation was good, with a total number of visitors somewhere between 10 000 and 15 000.

We concluded that we could have attracted even more participants and

achieved even more publicity, debate and awareness around the contents

of the Triennale if we had had more muscle. NAL had many valuable

contributors, but stood alone as the organizer. This was quite demanding

for everyone involved, not least for NAL’s administration, led by Hans

H. Halvorsen. The arrangement required a great deal of volunteer effort,

and the financing work was tiring.

We felt that that the Triennale had great potential, but in order to

take full advantage of it, we would need several co-partners and more

robust funding. The 2003 Triennale had a highly strained budget. NAL’s

project management and administration had made a considerable effort to

attract financial sponsors and support for individual events. NAL itself

provided a guarantee of NOK 240 000 to cover the remaining uncertainty

in funding.

The next Triennale. In 2005, NAL’s national committee began to plan

the 2006 Oslo Architecture Triennale. We agreed to continue to develop

the event as an architecture festival reinforcing Oslo’s image as an

‘architecture capital’, something to be reflected in the theme of the

Triennale. ‘Architecture and Culture’ was mentioned as an option. Our

target group would be the general public, politicians, architects and

planners. Our aim was to inform, create debate and draw attention to the

work of the architect.

We contacted the City of Oslo and signalled our interest in arranging

a housing exhibition that could be linked up to future triennials. NAL

applied for NOK 500 000 from the Ministry of Culture for further

planning of the 2006 Triennale. Norsk Form announced its interest in

participating as an organizer, and there was consensus on trying to

involve more co-organizers. Carrying out the 2006 Oslo Architecture

Triennale would be the responsibility of the new president and the

national committee, which took over in 2006.

English translation: Thilo Reinhard