BYENS LIVSFORMER

Scroll down for English

Min fremste relasjon til OAT er at jeg må kunne sies å være triennalens idémessige opphavsmann. Jeg satt i styret til Norske arkitekters landsforbund (NAL) i en periode ved tusenårsskiftet. NALs noe utydelige virke var for diffust og generelt. Organisasjonen gapte over litt for mange aktiviteter, i velmenende sosialdemokratisk ånd, tenkte jeg den gang. Min ideologiske motivasjon for å bli med var tre fanesaker: en internasjonal arkitekturtriennale, flere kvalitative arkitektkonkurranser og unge arkitekters fremtid.

Det skulle vise seg at det var den første saken jeg skulle bruke alt i alt rundt 2000 timer på, i tillegg til å drive min egen nystartede arkitektpraksis (en generøs takk til min familie herved).

Etter å ha tilbrakt tolv år borte fra min fødeby Oslo, hovedsakelig i utlendighet, føltes det provinsielt å flytte tilbake på siste halvdel av nittitallet. Den norske arkitekturdebatten om byen og urban utvikling virket på meg preget av 68’ernes selvforherligelse, slitne dogmer og moralske pekefingre. Denne velmenende generasjonen, som uten historisk sidestykke smidde samfunnet etter en rettferdighetsgestalt som gagnet dem selv mer enn noen andre.

I mangel av muligheter til å få oppdrag, begynte jeg å vandre langs markedets grøftekant og plukke opp oppgaver andre ikke ville ha. Samtidige duvet den foregående generasjon forbi i gilde farkoster, iført høyhalsede sorte gensere og markante arkitektbriller. Den dominerende debatten om byen var i stor grad tuftet på en sliten senmodernistisk moral om «den riktige rettferdigheten». For meg fremsto debatten som irrelevant og passé (mon tro hva de unge fremadstormende tenker om meg og min generasjon nå som vi er etablissementet?)

Etter mange år med arkitektstudier og praksis i Venezia, var internasjonale arkitekturbiennaler, kunstbiennaler og filmfestivaler blitt en naturlig del av mitt forhold til arkitektur, kunst og kultur. For venetianerne var arkitektur en del av livet og livet del i arkitekturen. Oslo fremsto som lite vital. Jeg savnet den faglige viraken og offentlige interessen. Ideen om en arkitekturtriennale i Oslo ble til en motivasjon for å bli med i NAL. Jeg tenkte at debatten rundt arkitektur burde tilhøre alle i samfunnet.

Ved å trekke internasjonale arkitektmiljøer til Oslo, ville vi få nye idéer, inspirasjon og nettverk. Kongstanken var å sette byens fysiske omgivelser på dagsorden med en nytenkende og mangfoldig agenda. Tanken ble til virkelighet. OAT #1 åpnet 15. september 2000: «Byens livsformer» var triennalens tema.

Noe av tidsånden bak den første triennalen fanges i et notat fra august 2000, der jeg skrev følgende styrende tekst (sitert i en lett redigert utgave):

OAT #1/2000 BYENS LIVSFORMER

ARKITEKTUR

uttrykker bruk og behov. Individer, familier, husholdninger,

interessegrupper, samfunn og nasjoner frembringer menneskenes mange

livsformer. Utvikling av byen må ivareta mangfoldet. Morgendagens by må

inneholde ROM for både individuell og kollektiv identitet.

Begrepet livsformer er valgt fordi det skal uttrykke noe generelt

og overgripende. På samme måte som ‘omgivelser’ er en generell

betegnelse på de fysiske strukturer som livet foregår innenfor, og er

omgitt av, er ‘livsformer’ ment som en betegnelse for hvordan livet

leves. Betegnelsen er altså ikke bare knyttet til boligsituasjon og

fritid, men omfatter også hvordan hele samfunnets produksjon og

utveksling skjer.

Tema for den første Triennalen vil være omstillingsproblemene som

bysamfunnet i dag står overfor. Endringer i teknologi, internasjonal

økonomi og rammeforutsetningene for å utøve politikk, skaper nye

betingelser for å formgi omgivelser. Dette viser seg i dag tydeligst i

bysamfunnene - i produksjon og organisering av næringsliv og i

kulturelle og sosiale endringer. Arkitektur er tolking av våre

livsformer.

Denne typen problemstillinger, smed ulik fokusering, står alle

større bysamfunn overfor, med ulike tilnærminger. Den europeiske byen

bærer med seg tradisjonsrike verdifull tradisjonell europeisk bykulturer

som stadig stilles overfor nye utfordringer. De nordiske byene

kjennetegnes av åpenhet og landskapsintegrering. Til samme tid er de

også sterkt preget av de velferds- og likhetsidealer som har

karakterisert nordisk politikk i de siste 50 årene.

Å løfte frem debatten rundt byens videre utvikling mener jeg har

stor verdi fordi den møter stadig nye utfordringer og byene får en

stadig større betydning. Diskusjonen i Norge har vært preget av

forenkling sett i forhold til den økonomiske, teknologiske og

sosiokulturelle kompleksitet som en utvikling av byen står i forhold

til.

På leting etter videre mulige utviklingsscenarier for byene

forvalter arkitektstanden viktig fagkunnskap som bør tre sterkere frem i

fokus.

Samtidsbyens tilstand er presist konstituert av det veldige kaos;

en fragmentert kompleksitet som inneholder et stort potensial for

videre utvikling, i mange forskjellige retninger. Den akselererende

globaliseringen skaper nye livsmønstre. Et økende omfang av

livsstilgenrer skaper nye behov som krever for en rikere artikulasjon,

innovasjon og bærekraftige løsninger i skjæringspunkter innenfor feltene

arkitektur og urbanisme.

Arkitektstanden bør være pådriver for å fremme nye muligheter i forhold til det økende mangfold.

Norge har mange utfordringer felles med de kontinental-europeiske

landene. Samtidig er den norske virkeligheten meget spesiell. Her

finnes ikke de akutte problemstillingene slik man ser i tette

demografiske områder i verden.

Befolkningstettheten på verdensbasis er ca. 40 personer per km2, mens den i Norge er 11 personer per km2.

All form for urbanisering i Norge relaterer seg visuelt til det

naturlige landskapet. Selv Osloregionen forblir en “by i skogen”. Denne

situasjonen med lav demografisk tetthet har forårsaket en skjødesløs

forvaltning av territoriet. Utbygging av de urbaniserte områder har ofte

skjedd etter overforenklede og tilfeldige fremgangsmåter.

…

De lokale og globale aspekter i byen påvirker vårt

sett å leve på. Behovene for kollektive referanser er konstante,

samtidig som individualitet innenfor det urbane rom stadig blir sterkere

som et resultat av eksisterende samfunnsmekanismer. Eksempelvis er det

tradisjonelle klare skille mellom hjem og jobb ikke lenger tydelig. Den

urbane strukturen må være i konstant utvikling for å kunne dekke et

økende spenn av både felles- og enkeltbehov.

Triennalen vil i sin første avvikling bli dedikert by-relaterte

tema i forhold til bestemte steder. Spesifikt vil det settes søkelys på

utviklingen av Oslo og potensialer for videre scenarier i forhold til

lokale og globale premisser.

I Triennalen settes søkelys på de byplan- og miljømessige

utfordringer hovedstaden står overfor gjennom presentasjon av scenarier

og visjoner som skal gi idéer, løsninger, forslag og innspill til den

videre utviklingen.

…

Utviklingen frigjør de arkitektoniske typologier, stadig

dukker nye hybrider opp, byens bilde endrer seg uavlatelig og i et

hektisk tempo. Oslo er ikke lenger symbolisert ved de gamle ikonene

Rådhuset og Holmenkollen. Utrolig mange strukturer inngår i arbeidet med

by formingen, og denne pluralisme er det vi forsøker å gripe fatt i og

gjøre til en kreativ ramme for den første Arkitekturtriennalen.

Hva tenker jeg tyve år etter?

OAT

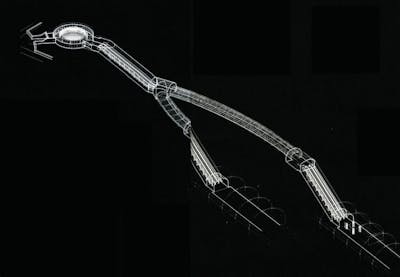

#1/2000 BYENS LIVSFORMER ble en fantastisk manifestasjon. Mange

enkeltmennesker og organisasjoner bidro med stor pasjon for denne første

triennaleavviklingen. Åpningen og konferansen var helt full og bar preg

av at noe nytt var i ferd med å skje i arkitektur-Norge. Selve

utstillingsdelen utgjorde det store løftet. Denne ble avholdt i et 400

meter langt tilfluktsrom under Nasjonalteateret stasjon. Man viste at et

av byens mange ukjente rom kunne brukes til flerfoldige aktiviteter og

at potensialet ved å utvikle nye strategier åpner for nye perspektiver

og muligheter. Mange unge norske arkitektkontorer bidro med faglige

nytenkende innspill og prosjekter. I tillegg ble det invitert et knippe

med utenlandske team som Kazuyo Sejima + Ryue Nishizawa, MVRDV, Studio

Rier Luigi Nicolin. Disse fikk i oppgave å utforme prosjekter og urbane

strategier for hvordan Oslo kunne vokse og utvikle seg til en god

fremtidsrettet by å leve i. Utopier og realisme ble knyttet sammen i en

mangfoldig vev av muligheter. For meg utgjorde triennalen den gang på

mange måter et vannskille i hvordan jeg så på Oslo.

I dette tyveårsperspektivet burde man tatt med seg flere av de

interessante tankene som kom opp. Innenfor boligsektoren har vi spesielt

sett mange tapte muligheter. Den byggede boligmassen avspeiler ikke

byens mangfold av etterspørsel. Politikere, offentlige byplanleggere og

utbyggere har vist liten evne til nytenkning innenfor boligarkitekturen.

Både den offentlig og private sektor må i større grad se på muligheten

for å utvikle nytenkende boformer, boligtypologier og nabolag der

helhetstenking har vært vektlagt.

Har OAT en berettigelse?

I

mine øyne er det viktig å eksperimentere mer. Samfunnets evne til å

utvikle arkitektur har i for stor grad blitt preget av juridisk

systemtenkning der man belønner det middelmådige, preaksepterte og

overfladiske. Juristen bør ikke være den som setter kriteriene for hvem

som er god nok arkitekt og hvordan man utvikler gode prosjekter.

Begrepet kvalitetssikring har i dag mer med feilsøking å gjøre, enn

med å virkelig utvikle kvalitet og sikre denne. Vi trenger en kritisk,

utprøvende, eksperimentell og fargerik arena som OAT.

«Skal humanismen gå i idealismens glemmebok?» spør Lars Saabye Christensen i sitt siste verk Byens Spor.

Alle snakker om bærekraft, men dette politisk korrekte tvangsordet

fremstår veldig hult. Det er ikke tvil om at keiserens nye klær

fremdeles er på moten. Når jeg ser meg rundt i Oslo, skjelner jeg mange

lettkjøpte konsensusholdninger, og grønnvasking med høy faktor har

virkelig frembrakt mange elendige byggverk. Noen av de mest omtalte

«bærekraftige» byggverkene fremstår som dårlig og sosialt uempatisk

arkitektur. Å skape gode arkitektoniske levekår i bærekraftig utforming

er krevende. Samfunnets ønske om bærekraftighet omfatter både fysiske

strukturer, mentale møteplasser og private rom som utformes med kløkt

tuftet på kvalitetstenking. Vi trenger å ta omgivelsene mer på alvor for

alle levende arter. Vi trenger mer empati, mer toleranse, mer tvil, mer

mangfold.

WAYS OF LIVING

Text by Reiulf Ramstad

My foremost connection with

the Oslo Architecture Triennale (OAT) is that I can claim to be its

conceptual author. For a period of time around the turn of the

millennium I sat on the board of the National Association of Norwegian

Architects (NAL). NAL’s somewhat unclear activities were too diffuse and

general. My impression at the time was that the organization, in the

well-intended spirit of social democracy, bit off a little more than it

could chew in terms of activities. My ideological motivation to join NAL

was based on three main concerns: an international architecture

triennale, more qualitative architectural competitions, and the future

of young architects.

As time would show, I was to spend a total of about 2000 hours on the

first of these causes, in addition to running my own newly started

architecture practice (herewith a heartfelt thanks to my family).

Having spent twelve years away from Oslo, mainly abroad, my return to

the city in the latter half of the nineties felt provincial. The

architectural debate in Norway about cities and urban development seemed

to be dominated by the self-glorifying generation of ‘68, worn-out

dogmas, and moral reproof; a well-intentioned generation that without

historical precedent forged society according to its own sense of

righteousness, benefitting themselves more than anyone else.

In the absence of opportunities for commissions, I started to pick up

assignments others did not want. At the same time, the previous

generation with their black polo-neck sweaters and conspicuous architect

glasses drifted past in flashy automobiles. The dominant debate about

the city was largely founded on the stale late-modernist ethic of

‘proper justice’. To me, the debate seemed irrelevant and passé (but I

wonder what the young and aspiring think about me and my generation, now

that we are the establishment?)

After many years of studying and practicing architecture in Venice, a

natural part of my relationship with architecture, art and culture

involved international architecture biennials, art fairs and film

festivals. For the Venetians, architecture was a part of life, and life

was enmeshed with architecture. Oslo appeared to be a city of little

vitality. I was missing the professional bustle and public interest. The

notion of an architecture triennale in Oslo motivated me to join NAL. I

felt that the debate about architecture should belong to all of

society.

By attracting international architectural communities to Oslo, we

would gain new ideas, inspiration and networks. The central idea was to

spotlight the city’s physical environment with an innovative and

diversified agenda. The idea became a reality. OAT #1 opened on 15

September 2000. The theme of the Triennale was ‘Ways of Living’.

Some of the spirit behind the first Triennale is captured in a note

from August 2000, in which I set out the following guidelines (slightly

revised):

OAT # 1/2000 WAYS OF LIVING

ARCHITECTURE

expresses need and use. Individuals, families, households, interest

groups, societies and nations foster many different ways in which human

beings live. Urban development must safeguard this diversity. Tomorrow’s

city has to incorporate SPACE for both individual and collective

identity.

The phrase ‘ways of living’ has been chosen in order to express

something general and overarching. Just as ‘sourroundings’ is a general

term for the physical structures in which life takes place and by which

it is framed, ‘ways of living’ is intended as a term denoting how life

is lived. This means that the term not only relates to housing

situations and leisure activities, but also encompasses the ways in

which production and exchange take place throughout society.

The theme of the first Triennale will focus on the restructuring

issues faced by urban societies today. Changes in technology, the

international economy and the general framework underlying political

policy create new conditions for shaping the environment. Today, this is

most evident in urban communities – in the production and organization

of businesses and in the changes affecting cultural and social arenas.

Architecture is the interpretation of our ways of living.

All larger urban communities face these types of issues, with

varying focus and various approaches. European cities represent valuable

traditional urban cultures that are increasingly faced by new

challenges. Nordic cities are distinguished by openness and landscape

integration. At the same time, they are also strongly shaped by the

ideals of welfare and equality that have characterized Nordic politics

over the past 50 years.

Raising the debate about the future of urban development is of

great value, I believe, because cities are constantly facing new

challenges and are becoming increasingly important. In Norway, the

discussion has been characterized by an oversimplification in relation

to the economic, technological and socio-cultural complexity associated

with urban development.

In the search for possible future development scenarios for our

cities, the architectural community is able to draw on important

expertise that should come into stronger focus.

The current state of our cities is, if anything, distinguished by

a tremendous chaos; a fragmented complexity that offers great potential

for future development, in many different directions. Globalization is

accelerating and creating ever new life patterns. A widening spectrum of

distinct lifestyles entails new requirements that demand richer

articulation, innovation and sustainable solutions in the intersection

between the fields of architecture and urbanism.

The architectural community should be a driving force in promoting new opportunities in connection with the growth in diversity.

Norway shares many of the challenges faced by continental

European countries. At the same time, Norwegian reality is quite unique.

Here, we are not confronted with the acute issues that can be seen in

densely populated areas in the world. While the global population

density is approximately 40 people per km2, that of Norway lies at 11

people per km2.

In Norway, all forms of urbanization relate visually to the

natural landscape, and even the Oslo region remains a ‘city in the

woods’. This low demographic density has led to careless management of

the territory. The development of urbanized areas has often been based

on oversimplified and random methods.

…

The local and global aspects of the city affect the

way in which we live. There is a constant need for collective

references, while individuality within the urban space at the same time

becomes increasingly more pronounced as a result of existing social

mechanisms. For example, the traditionally clear distinction between

home and work is no longer unambiguous. The urban structure must be in

constant development to be able to fulfil the increasing range of both

communal and individual needs.

In its first implementation, the Triennale will be dedicated to

city-related topics tied to particular locations with specific focus on

the development of Oslo and the potential for future scenarios in

relation to local and global premises.

The Triennale will spotlight urban planning and environmental

challenges facing the capital by presenting scenarios and visions

designed to spawn ideas, solutions, proposals and input for further

development.

…

Development leads to the liberation of

architectural typologies; new hybrids are constantly emerging, the

cityscape is changing perpetually and at a hectic pace. Oslo is no

longer epitomized by former icons such as City Hall and Holmenkollen.

Work on urban design involves innumerable structures, and it is this

pluralism we are attempting to address and utilize as a creative

framework for the first Oslo Architecture Triennale.

What do I think twenty years later?

OAT

#1/2000 WAYS OF LIVING materialized into an extraordinary event. Many

individuals and organizations contributed with great passion to

facilitate this first Triennale. The opening and the conference were

filled to capacity and revealed that something new was about to happen

in Norwegian architecture, with the main exhibition being the core

attraction and force. It was held in a 400-meter long shelter beneath

Nationaltheatret railway station. This made it possible to show that one

of the city’s many unknown spaces could be used for numerous

activities, and that the development of new strategies opens up the

potential for new perspectives and possibilities. Many young Norwegian

architecture firms contributed with innovative professional input and

projects. In addition, a small number of foreign teams were invited,

including Kazuyo Sejima + Ryue Nishizawa, MVRDV, and Pierluigi Nicolin.

These were given the task of designing projects and urban strategies for

Oslo to grow and develop into a forward-looking city with a good

quality of life for its citizens. Utopias and realism were united in a

diverse web of possibilities. For me at the time, the Triennale in many

ways represented a turning point in how I viewed Oslo.

Has OAT #1 had any effect?

This

is not easy to ascertain, of course, but the Triennale undoubtedly

helped ignite some sparks of enthusiasm and innovative thinking for the

future development of the city. Oslo has become a richer, more diverse

city to live in. Undoubtedly, there have been many positive changes in

our city, although major challenges remain on the horizon, both locally

and globally. The general culture is infiltrated by local and global

trends. Oslo has gained faith in its ability to grow into a medium-sized

European city with all the qualitative advantages of an urban culture.

Furthermore, it was not exactly a disadvantage that this period was

characterized by an exceptionally strong economy. In 2020, the

increasingly recognized World Happiness Report has ranked not only

countries, but also cities. Here, Oslo is positioned as one of the

world’s best cities to live in. I shall be careful to specify the degree

to which the Triennale has been a concrete factor, but one can assume

that it has been a positive aspect for many professionals during these

twenty years.

A number of the interesting ideas that arose in this 20-year

perspective should have received more consideration. The housing sector

in particular has sustained many missed opportunities. The aggregate

housing stock does not reflect the city’s diverse demands. Politicians,

government planners and construction companies have shown little

willingness for innovation when it comes to residential architecture.

Both the public and the private sector must take a closer look at the

prospect of developing more innovative forms of housing, housing

typologies and neighbourhoods with an emphasis on holistic thinking.

Does OAT have legitimacy?

In

my view, it is important to experiment more. The ability of society to

develop architecture has been far too prone to systemic legal thinking

that rewards mediocrity, entrenched views and superficial thinking.

Lawyers should not be the ones to determine the criteria for who is a

good enough architect and how to develop quality projects.

Today, the concept of quality assurance has more to do with

troubleshooting than with the actual development of quality and its

safekeeping. We need a critical, experimental, exploratory and diverse

arena such as OAT.

‘Will humanism sink into the oblivion of idealism?’ asks Lars Saabye Christensen in his latest novel Echoes of the City.

Everyone talks about sustainability, but this politically correct

verbal straitjacket appears to be quite hollow. There is no doubt that

the emperor’s new clothes are still in vogue. When I take a look around

Oslo, I see many run-of-the-mill solutions based on consensus, and many

truly dreadful buildings are the result of greenwashing of the highest

order. Some of the most talked about ‘sustainable’ constructions stand

out as poor and socially indifferent architecture. The creation of good

architectural living conditions with a sustainable design is a demanding

task. Society’s desire for sustainability includes both physical

structures, mental meeting places and private spaces designed with a

view to quality. We need to take our environment more seriously for all

living creatures. We need more empathy, more tolerance, more doubt, and

more diversity.

English translation: Thilo Reinhard